Safeguarding our Food Supply in the Face of Climate Change

There is a silent extinction underway in the world of plants.

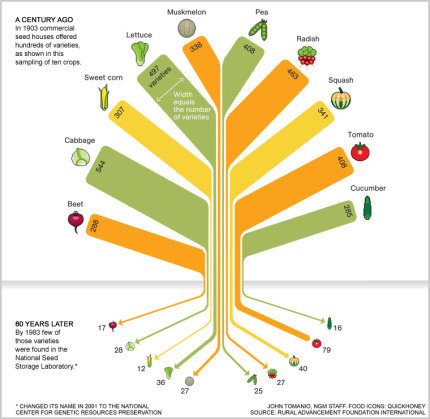

We’ve all heard of the troubling mass extinction of animal life, so it may come as a surprise to hear that seeds are in even deeper trouble. Since the turn of the century, 93% of US seed varieties have gone extinct and with them the diversity of our meals. As clearly shown in the infographic (left) published by National Geographic’s John Tomanio, nature’s tastiest gifts have dramatically disappeared across the past century. According to the UN Food and Agriculture Organisation (the FAO), 75% of the world’s food is now generated from only 12 plants and five animal species.

This means not only less interesting dishes for our dinner plates, but has implications for global food security. With projections of 9 billion mouths to feed by 2050, the time is now to safeguard what remains of agricultural genetic diversity. An urgent race is underway globally to collect and bank seeds that may hold within them the genetic keys to drought or pest resistance – an insurance policy for safeguarding our future food supply in a climate-changed world.

‘Yellow flower’, ‘guinea pig fetus’ and ‘pumas paw’ are rich and unusual descriptions of just three of the over four thousand potato varieties grown today in the starchy tubers country of genetic origin, Peru. In Peru, farmers bred successive generations of what was once a poisonous plant, slowly developing it into the edible potato, each variety adapted to its local climate. Today, the homogenous potato that we recognise is the most-eaten vegetable in the United States, and the third most important food crop in the world after rice and wheat in terms of human consumption.

In considering the case of the potato, a trip to the supermarket is proof of the lack of diversity. Our most common experience is a choice between two uniform varieties: the russet potato or the sweet potato (which isn’t actually a potato). Familiar, unsurprising and homogenous. This pattern is being repeated globally. All over the world, we are now eating the same ‘popular’ varieties of corn, potatos, bananas, wheat, and more – replacing local crops. While modern varieties have been bred for taste, pest-resistance and high yields, our agricultural biodiversity has been vastly depleted and wild species are being lost.

How do we save what remains of global plant diversity?

One answer is seed banks. There are now more than 1,750 seed banks worldwide, with 130 of these holding more than 10,000 accessions (collections of plant material) each. In Lima, Peru, sits one important example: the International Potato Center (Centro Internacional de la Papa, CIP). Its genebank maintains a collection of over 80% of the world’s native potato and sweet potato cultivars, with in vitro germplasm available for international breeding programs.

Potatoes in space?

The CIP, just like Matt Damon’s botanist character in “the Martian” recently partnered with NASA to develop potatoes able to grow in the inhospitable climate of Mars. Their test-bed is the soil of the Peruvian desert. This fascinating example shows the importance of saving seeds in order to be able to access their genetic material. Seed germplasm may hold the key to developing a new ‘space’ potato adapted for a drier, hotter climate in many regions.

Drilled into the side of a mountain in Norway lies the last stand against the loss of seed diversity: the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. Opened in 2008, Svalbard stores backup copies of other seed collections in its naturally chilled, earthquake-free zone 400 meters above sea level. Designed to hold 4 million seed samples on permanent thaw, it is nicknamed the “doomsday vault”. Svalbard is a literal seed fortress: built to withstand global catastrophes from war to sea level rise.

Despite it’s purpose as a ‘last resort’ backup, Svalbard has already experienced its first withdrawal less than ten years after opening. What catastrophic event prompted this withdrawal of lost seeds?

The Syrian Civil War

The ongoing Syrian war has not only carried a heavy human toll. Aleppo, Syria’s capital, was also the location of one of the most important seed banks in the world, the International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA). It stored more than 135,000 varieties of wheat, fava bean, lentil and chickpea crops, as well as the world’s most valuable barley collection.

In 2011, the seed bank relocated from Syria to Lebanon’s capital Beirut, to flee the ongoing civil conflict. Four years later, ICARDA withdrew nearly 116,000 seeds from the Svalbard vault – safely rebuilding its collection of globally important seeds. It’s drought-tolerant seeds may prove critically important in a hot and dry climate future. This was a win for seed conservation, and proof of concept for the global seed bank: saving seeds that would otherwise have become a wartime casualty.

Despite a global push to preserve the world’s seeds, the FAO reports that of the total 7.4 million seed samples conserved worldwide in 2010, national government genebanks conserve the vast majority (approximately 6.6 million) of which 45% are held in only seven countries (down from twelve in 1996). This increasing concentration of seed genetic diversity raises important questions about access and control, especially since seed depositors are, as is the case for Svalbard and CIP, required to sign a legally binding International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture. This subjects the seed’s genetic resources to commercialization by other parties and raises important questions.

Should seed genetic information – which evolved with life itself – be patented?

Since the commercialization of transgenic crops in the mid-1990s, the sale of seeds has become dominated globally by Monsanto, DuPont and Syngenta.

We owe thanks to previous generations of patient Peruvian potato farmers for our russet potatoes and potato fries. If a biotech company makes a slight genetic change to a potato to create a new variety, should they then be allowed to patent it and control the sale and profits acquired? This is the basis of a raging debate in the seed world. In the past, seeds were a communal, ‘global commons’ resource. Today seeds are increasingly controlled by transnational agribusinesses such as Monsanto.

It is therefore essential to acknowledge that whoever holds the keys to seed resources can wield a great deal of power over the global food supply, and by extension, farmer’s rights.

Grass-roots seed saving has emerged as a response to the loss of local control over seeds and farming practices. Seed Freedom is a global movement organized to fight back, urging “civil disobedience to end seed slavery” with a global “Call to Action 2016” planned this October. Here in the US, the nonprofit organization Seed Savers Exchage based in Missouri maintains a collection of 20,000 seed varieties in an underground freezer vault, also backed up at Svalbard. Seed Savers Exchange members are able to share and save their homegrown seeds with each other via their online Seed Exchange.

Community seed banking has become a tool of defiance against industrialized high-input, ecologically destructive agriculture, and a means of independence and empowerment. It protects a community and a country’s seed sovereignty towards a self-reliant, sustainable agricultural future.

According to the United Nations “World Urbanization Prospects Report”, 66% of the world’s population will live in cities by 2050 with an even more limited connection with agriculture. Therefore, it is important to propagate a widespread awareness and understanding of the significance of seed heritage and agricultural biodiversity, in hopes of preserving the diversity of seed varieties on our planet – an essential tactic in the fight against climate change.

As individuals and consumers, we can each encourage the popularization of heirloom varieties – as greater use of germplasm is linked to conservation. We have purchasing power to buy when possible locally produced, local varieties of fruit and vegetables, helping to popularize the diversity of our food supply. We can choose to support public organizations in their seed conservation efforts, and community seed banking and organic farming organizations working in developing countries. In doing so, we can all help to secure the diversity of our global seed supply, and ultimately our food security.

*Trendster is a voluntary, crowd-sourced initiative facilitated by SUMA Net Impact. It does not represent the collective views of Columbia University, the Earth Institute or Net ImpactThis post was originally published on the SUMA Net Impact website.